Let’s take a train ride to the past and talk about the INCO slag pour.

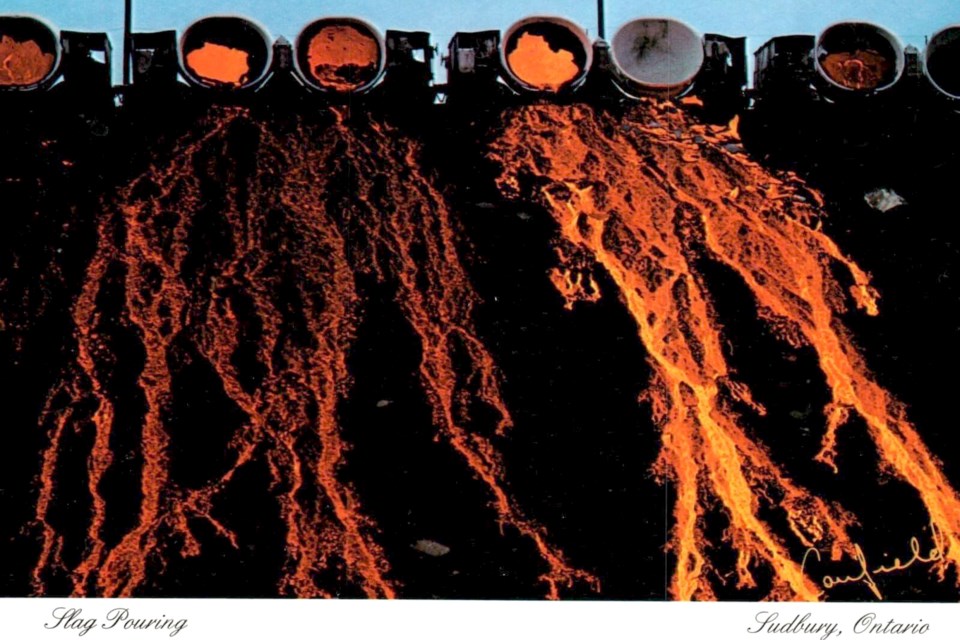

What was once a familiar sight to residents of the Nickel Capital, and attracted tourists from far and wide, were those long fiery rivers of lava surging forth from a train of pots and cascading down the manmade mountainside of the slag dump, lighting up the night sky with its vermilion glow.

For those of us lucky enough to have lived here during those times, this was one of the perks of living in a mining town.

Slag is what remains after most of the precious metals (nickel, copper, silver, zinc and gold) are removed. Slag is the waste. Thin pieces of slag are not nearly as hard as rock, and break up quickly and easily, almost like glass. In fact, on a rainy evening, black chunks of slag are known to sparkle like diamonds.

The pouring of this molten metal, at temperatures up to 1,300 degrees Celsius, used to be a common sight in Sudbury’s West End. Unfortunately, though it is still done 24/7, every day of the year, most people never see it.

However, it remains an important aspect of our memories as residents of the Nickel City, a communal memory (if you will) which links everyone whether they had a direct connection to the mining giant or not.

Let us travel back to the summer of 1966. More than 10,000 tonnes of molten slag is coming out of the Copper Cliff smelter every 24 hours, seven days a week. In the 50 years (give or take a few) that this sight has been entertaining the public, more than 130,000,000 tonnes of slag has been dumped across the 500-acre disposal area east of the smelter.

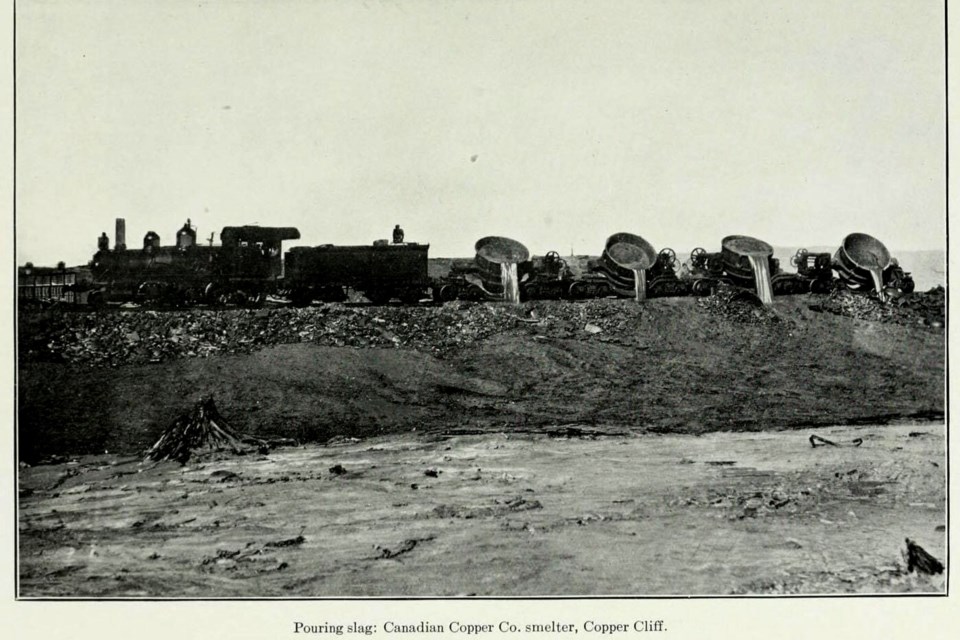

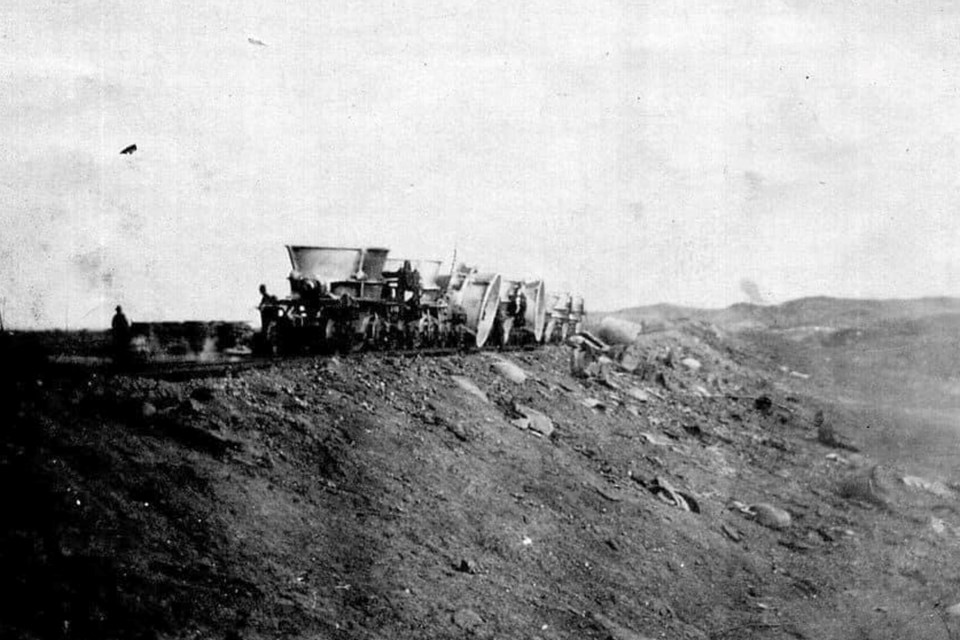

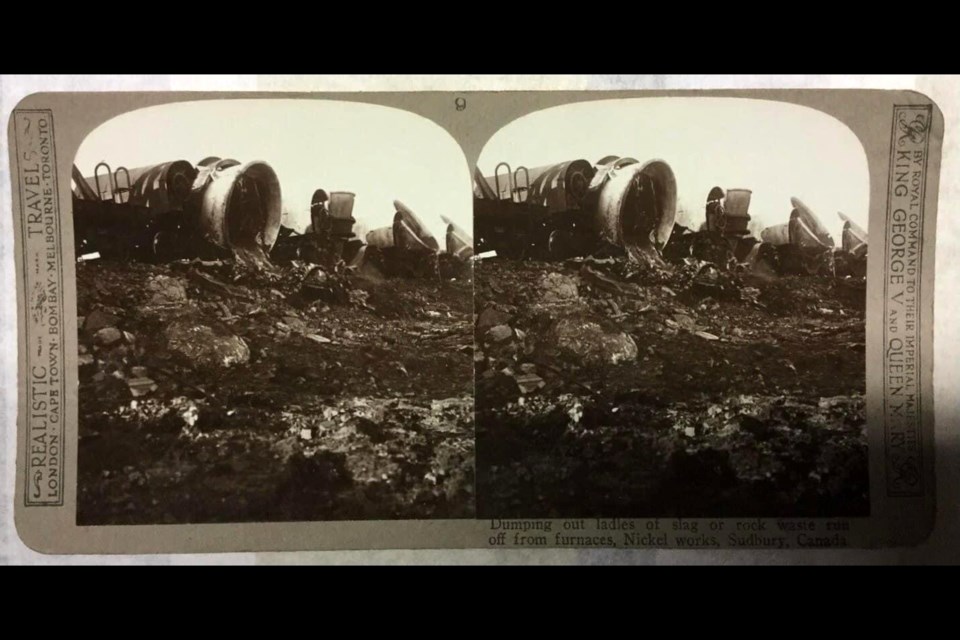

Of course, the disposal of such a huge volume of waste material in a safe and orderly manner requires highly efficient organization. Every half hour around the clock, the trolley locomotives will haul a train of lime-whitened slag pots from the east end of Copper Cliff Smelter, bound for the slag dump. The average train carries 22 pots, each holding 16 tons of slag with a gross weight of 50 tons.

Meanwhile, an empty train is just entering the west end of the smelter where it will soon be spotted at the reverberatory and blast furnaces being loaded with slag, so that a continuous movement of slag is being maintained. Three trains of pots are always on the go.

The pots are dumped electrically. A pail of water is then thrown into each pot to snap out the “skull” of solidified slag (metals that sink to the bottom of slag bowls, remaining there after the hot material is dumped). The skulls are dumped every day to return "capacity" to the bowls.

Three main dumps are in regular use in the disposal area. The No. 2 dump, facing north toward Sudbury, No. 3 dump, facing east toward the West End, and No. 5 dump, the highest at the time, facing back toward the Smelter. The No. 4 4 dump, which faces toward the current Highway 144, is used only sparingly, as is the No. 1 dump, facing Gatchell. The main dumps are used in rotation to allow for track-moving operations and adverse wind conditions.

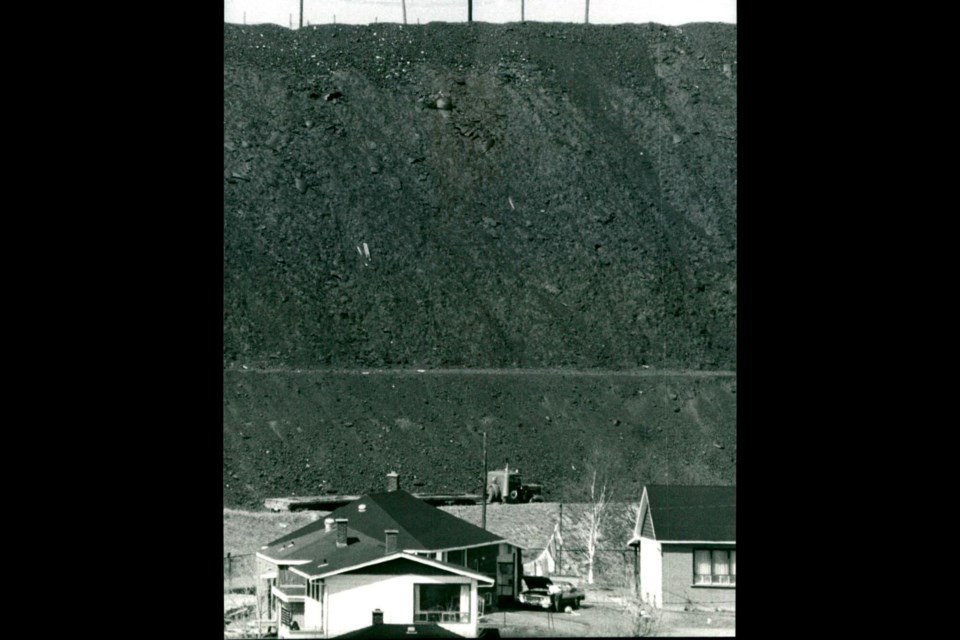

As the slag dumping operation proceeds, the face of the dump steadily grows away from the slag train track until the pots can no longer pour their molten cargo. Then the slag track, complete with trolley wires and poles, has to be moved over and relocated. There's more than five miles of track on top of the slag dump to be maintained, and track shifting takes place every three or four days. As well as spreading out toward the perimeter of the disposal area, the dump has been slowly growing in height over time.

Many a time, fathers and mothers could be found piling as many children as they could squeeze (often in their PJs) into their cars for a trip to see the slag dumping, with a side trip to Deluxe or Dairy Queen. It was amazing how close one could actually get, especially if one arrived early enough to get a good spot. Once you were to step outside of the vehicle, one could feel the intense heat as the sky would light up for miles around.

Sudburians proudly drove visiting family members and out-of-town guests to park in the area that is now Big Nickel Mine Road and take in the colourful spectacle. The glow of the burning slag pile was definitely a sight to behold. Spectators would never tire of seeing 16-tons of slag tipped over the edge (as if by a curious cat), spilling their fiery cargo downhill.

Some others among you may remember the parking lot overlooking the slag dump was called "the passion pit" and that it drew people from all over the city to watch slag pouring (yeah, right).

That area where people would park their cars to watch slag being poured, was an integral part of growing up for the young people of Sudbury. Couples drove from all over the Nickel Range to "watch" the slag pouring, and enjoy their very own “paradise by the dashboard light”, Sudbury-style.

In fact, some couples actually knew the timing of when slag would be dumped, especially on those cold, cold winter nights with the windows all fogged up and would then never be hassled by the police.

In addition to those who travelled from all over the region to marvel at the slag being poured, many who grew up in Gatchell would recall the wonder of only having to look out the window of their homes to see the slag being poured. Even a local motel near the slag heaps posted a sign bragging that slag dumping could be seen from there.

Of course, for a time there was a completely novel way to bring the slag pour to the people (instead of bringing the people to the slag pour). Many of you won't believe it, but in the early days of television in Sudbury, families used to hunker down around their tiny television sets to watch the slag pours in Copper Cliff. As an aside, the station went even farther for a time and televised the shift changes at Frood Mine as well.

At CKSO in the days before instant satellite communications, filling the 12 hours of television per day promised by the station’s founders was at times agonizingly difficult — hence the slag pour.

Back in 1996, Bill Kehoe (the very first news anchor on CKSO) recalled, “We had to haul our huge camera up to the newsroom on the southwest corner of the station up on Larch Street, point out the window so people at home could watch the INCO slag pour in Copper Cliff. That was a huge entertainment draw those days.”

He also recalled that they “also used to take the camera up to Wilf Woodill’s (station general manager) office in the northeast corner and point it up Frood Road. We'd see the afternoon shift coming off at Frood and people would be sitting at home trying to spot Dad's car."

For certain, the landscape of the Sudbury Basin was never something locals would ever brag about back then. Remember the jokes about why the Apollo astronauts were here? People outside of the community considered Sudbury a wasteland, a moonscape. However, the slag-pour, this end result of the mining process which did much damage to the environment around us for most of the 20th century, also reminded us of the beauty found from taming the demon ore (it was originally called “kupfernickel” which could be very loosely translated to “copper demon”).

Over the last five decades, and thanks to the efforts of Keith Winterhalder (he discovered the scientific formula to develop a form of lime base that would allow trees and vegetation to grow and prosper rapidly across Greater Sudbury’s rocky landscape), the dirty and desolate hills of slag have been transformed into hills of emerald green by thousands of community volunteers, and city and industry partners who applied lime and fertilizer across the barren landscape.

In recent years, the slag pouring has now been done out of sight of residents (which of course makes it out of mind for most Sudburians). Slag is still being poured at four dumps at Vale, none of which are visible from the road as they once were. Blocking the view are those very hills of the past now covered with green grass and trees. Most people who were around during the glory days of the slag dump would relish revisiting the scene for nostalgic reasons, but, unfortunately, short of brief glimpses along the Big Nickel Mine Road-Highway 144 corridor, it remains a warm memory.

Well dear readers, we have briefly revisited the flaming visions of the fiery refuse that remained from the industry that built our community and fascinated so many people. Now, don’t slag me for asking but I please share with us your memories of going to visit the slag dump with your family, friends or boyfriend/girlfriend by emailing [email protected] or [email protected].

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program/